Circus in Backfields

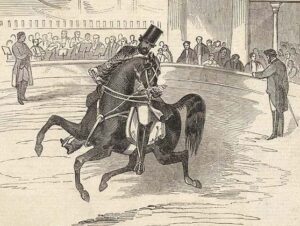

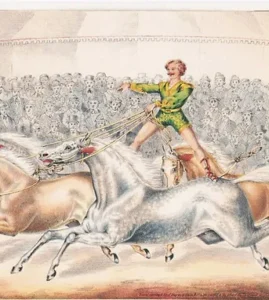

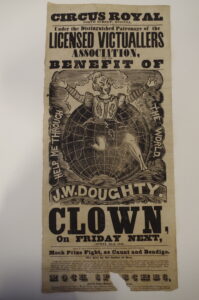

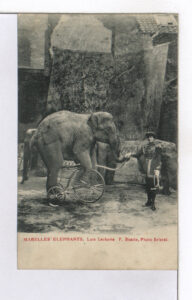

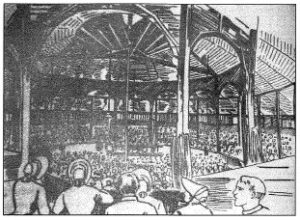

Opposite Lakota is a small lane called Backfields, reached by the lane from the Full Moon Inn, now called Moon Street. The riding school is considered to be one of the first circuses, built on the site of a circular yard of riding stables. the first riding school in Bristol, opened by RC Carter in 1761. Following a similar riding school in London, the riding school began to put on popular public displays of equestrian showmanship and other events, such as bare-knuckle boxing battles and acrobatics.

In 1790 it was superseded by a purpose-built wooden amphitheatre, and in 1824 it was rebuilt again into a more modern and sophisticated amphitheatre.

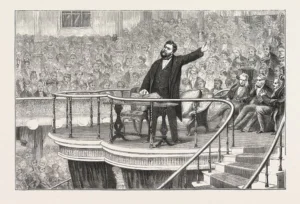

In 1861, so many people turned up to hear the celebrity preacher Charles Spurgeon at the opening of City Road Baptist Church that the meeting was relocated to the circus arena. After 2000 people were admitted, the doors had to be closed to prevent dangerous overcrowding, provoking a riot which badly damaged the building.

The building was eventually sold to the Salvation Army who named it the Salvation Circus, using it until it burned down in 1885.

“A more unexpected venture was made by G. W. Harris who on

6 October 1873 opened the old Circus in Moon Street, at the back

of Stokes Croft, which had been built for James Ryan in 1837.

For over a decade now it had been only occasionally used, as

travelling circuses developed tenting techniques, and there were

plenty of precedents in the provinces for such a change of use…

…The Era reported it generally well attended during Harris’s management. Unfortunately it changed hands in January 1875, and on the reopening night the performance came to a stop after an hour, a number of the artists advertised having failed to appear.

The audience demanded their money back, and this being refused, they rushed the Manager, “many of those present arming themselves with portions of the seats, which were broken up.” The Manager hastily sought police protection, and a frustrated mob commenced throwing stones, and broke every pane of glass in the building, and a scene of great disorder prevailed in the neighbourhood until a late hour. A fortnight later the Era reported the building “announced for

reopening under fresh Management and a new Title“: the Britannia. But the damage had been done-in every sense-and at the end of the month the new lessees had to cancel all contracts. A Derby manager called Stoner advertised that he would reopen the Britannia, but his intentions came to nothing; a further attempt early in 1877 lasted one month, and about 1880 the building was bought by the Salvation Army.”https://bristolha.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/bha044.pdf

- For The Benefit Of Pablo Fanque, The Greatest Victorian Showman: https://londonist.com/london/history/for-the-benefit-of-pablo-fanque-the-greatest-victorian-showman

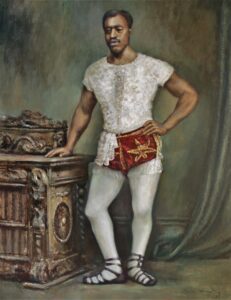

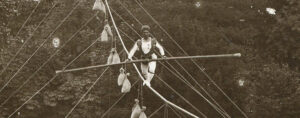

Pablo Fanque, Circus Owner, Equestrian,

Tight Rope Walker, Acrobat: https://www.africansinyorkshireproject.com/pablo-fanque.html

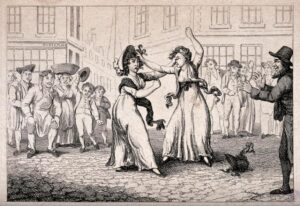

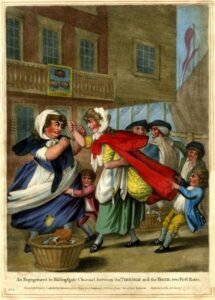

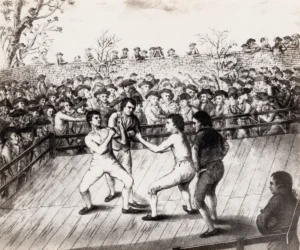

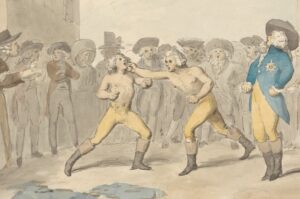

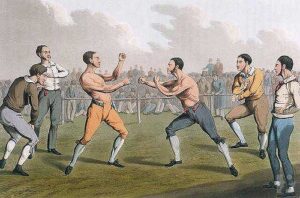

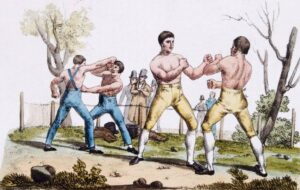

Bare-knuckle boxing

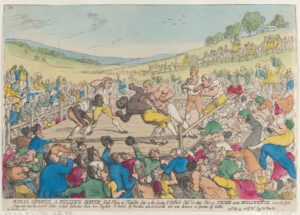

The 18th century saw a boxing craze sweep Britain. Boxing could be an informal way to settle disputes, which gathered a crowd who placed bets, and there were some huge matches around the country with enormous prizes for the participants.

A prize of £50 in the 1780s would be worth £11000 in today’s money, split between the fighters with 2/3 going to the winner. Prizefighters could expect to buy a house and retire after a good season.

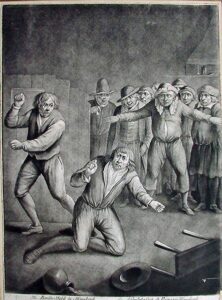

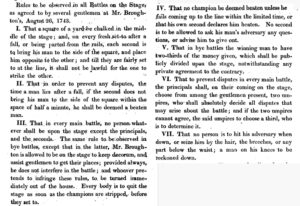

Bare-knuckle boxing was quite a brutal sport, sometimes lasting 30 rounds or more, although it was regulated with rules to ensure fairness for the people betting.

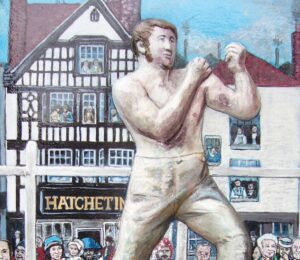

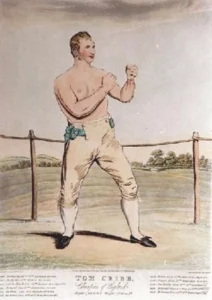

Tom Cribb was a very famous boxer from Bristol, commemorated by a plaque in the Hatchet Inn, where fights were held. Fights were also held in Backfields, behind the Full Moon Inn on Stokes Croft.

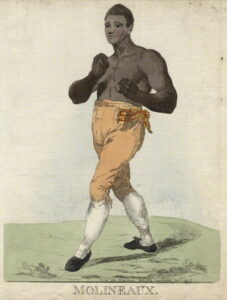

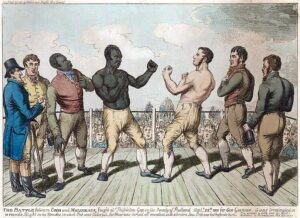

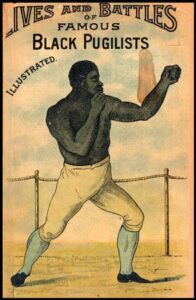

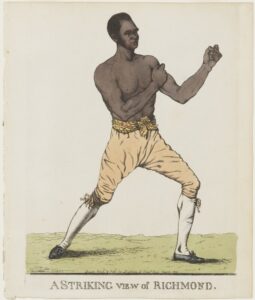

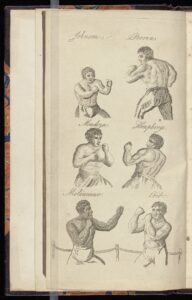

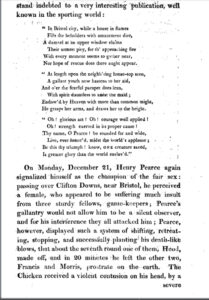

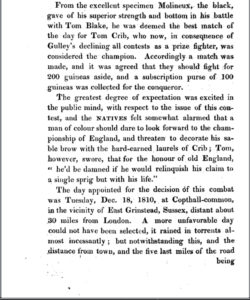

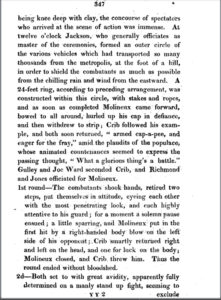

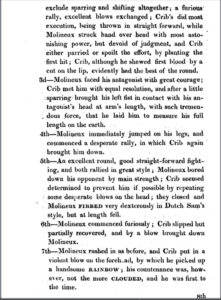

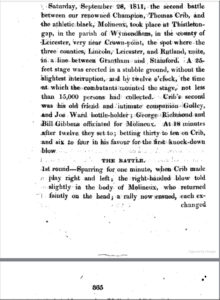

Tom Cribb was famous for fighting Tom Molineaux twice, a fight which brought tens of thousands to watch it. Tom Molineaux was an escaped slave from Virginia, who travelled to the UK to seek his fortune as a boxer. He was trained by Bill Richmond, who became one of the first sporting superstars.

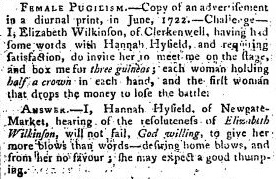

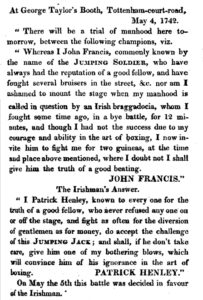

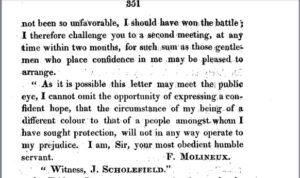

Below are some scans from Pancratia: Or a History of Pugilism from 1812. I love the blow-by-blow accounts which seem to have the excitement of radio sports commentators. I find the polite diss- contest hilarious:

“nor am I ashamed to mount the stage when my manhood is called into question by an Irish braggadocia… I now invite him to fight me for two guineas… where I doubt not I shall give him the truth of a good beating”

“I… do acept the challenge of his Jumping Jack; and shall, if he don’t take care, give him one of my bothering blows, which will convince him of his ignorance in the art of boxing”

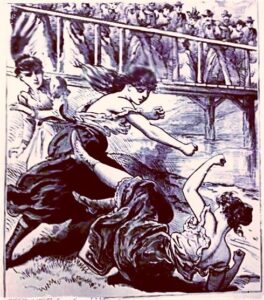

- Women’s Boxing: A Georgian Novelty Act by Julia Herdman: https://juliaherdman.com/2017/05/20/womens-boxing-a-georgian-novelty-act/

- Female Bare-Knuckle Boxing in Georgian London: A Hidden and Forgotten History: https://medium.com/flamma-saga/female-bare-knuckle-boxing-in-georgian-london-a-hidden-and-forgotten-history-5b6a502f3558

- The Bristol Boys: An article about the four 18th century Bristol boxers celebrated by a plaque in the Hatchet Inn: https://francesca-scriblerus.blogspot.com/2016/04/the-bristol-boys-bare-knuckle-champions.html

- Pugs, Roos and Amazonians: Some Lesser Known Boxing Matches of the Eighteenth Century: Overview of 18th century boxing: https://francesca-scriblerus.blogspot.com/2021/06/pugs-roos-and-amazonians-some-lesser.html

18th Century Female Bruisers: https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2016/06/21/18th-century-female-bruisers/

- Boxing: When a freed slave fought a sporting star: The story of Tom Molineaux: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-27632884

A Fighter Abroad: In 1810, a freed slave named Tom Molineaux fought in one of the most important fights in the history of boxing. This is his story

https://grantland.com/features/brian-phillips-boxing-career-freed-american-slave-tom-molineaux/

- Bill Richmond, who trained Tom MolineauxL https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/sporting-heroes/bill-richmond-the-pioneering-pugilist/

- Pancratia: A History of Pugilism published in 1812 – PDF (20MB): Pancratia or a history of Pugilism – PDF

Stokes Croft Brewery

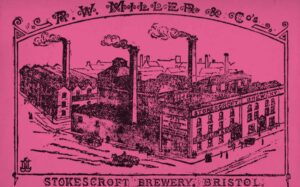

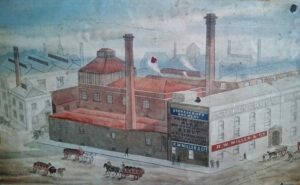

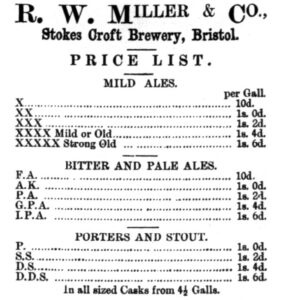

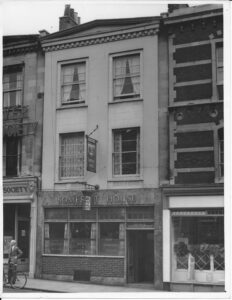

The Lakota inhabits the last remaining buildings of Stokes Croft Brewery, owned by RW Miller & Co from 1893. Lakota is in the former Victorian malthouse, and the tall factory buildings extended across Moon Street to Stokes Croft.

“The brewery… stands in a splendid business position, having a large frontage to Stoke’s Croft. At the entrance there is a newly-erected porch of freestone, artistically carved, and having the name of the firm emblazoned upon it in picturesque lettering. Entering through two new doors, constructed of specially-selected pitch pine… the visitor finds himself in a lobby made of the wood mentioned previously, and having a pretty tessellated tiled pavement. A door, set off with Muranese glass, leads into the brewery; but taking a turning to the left, one obtains access to the counting-house. The two folding doors leading to it are pretty in design, the upper parts being of cathedral glass, with rural scene in the centre.

The counting-house is a well-lighted room, the recent alterations having considerably enlarged it… The apartment is lighted with the well-known Wenham burners – one also being in the porch – and five standards supply ample light for the clerks at the desks. The fittings of the office are of walnut and oak, and have very handsome appearance.

Opening out at the far end of the room is the telephone room, lavatories, and the strong room. At the end of the counter a screen of pitch pine, with Muranese glass, is constructed, and this leads to the travellers’ office and private room. The former is a lofty apartment, and is designed for the use of the large staff of travellers and collectors in the employ of the firm. The walls are cased with pitch pine, giving the room, which is over 30ft in height, an imposing appearance. From here a well constructed staircase leads to the principals’ private rooms and the sample room. On the right hand is the principals’ private office, and on the left is a large and spacious room, elegantly fitted up, for the use of Mr R. W. Miller.

From this apartment access may be obtained into the brewery; but before this is visited it is well to take a peep into the laboratory, which is the sanctum of Mr J.H. King. This gentleman holds the important position of brewer and manager, and comes to Bristol with the highest credentials, having had many years experience at Exeter and the Ale Metropolis, more familiarly known by the name of Burton. The art of brewing has now become science with modern brewers, and therefore the necessity of knowledge of chemistry is only too apparent. In Mr King’s laboratory are all the appliances for carrying out the testing, &c., so necessary in the manufacture of high class ales. Under the care of Mr King, a visit to the brewhouse discloses some interesting particulars.

Entering the mashing-room, one notices the mashing plant, which was designed and fitted by Messrs G. Adlam and Son, the well-known engineers of Bristol. One of Steele’s mashing machines and inside rakes, similar to those used in most large breweries, is here; the adjoining compartment, which is called the copper room, has a spacious underback with coils, and adjoining it is a large copper for boiling the wort. Close to the copper is the hop back, from whence the wort is pumped to the cooling room, which is at the top of the building.

Ascending a flight of stairs, the malt room is reached, outside which there are two large mashing backs for heating the liquor. The malt room is filled with sacks of malt, and in the corner is a bin, into which the grain is placed, and from there it runs to the crushing mill on the next floor, and thence, by series of ‘Jacob’s ladders’, is conveyed to the grist case in the centre of the room. From there is taken into the mashing tub below. The cooling room is situated at the top of the premises, and is a large building some 40 or 50 feet square, and in this are placed coolers. From receptacles wort proceeds to one of Lawrene’s refrigerators, where it is cooled and conveyed to the fermenting vessels, which are placed in the room beneath. Here a gas engine is employed to drive what is called the ‘rousing’ machinery.

Passing this important part of the building one comes to a large apartment, really apart from the main structure, and the delicious scent once apprises the visitor of the fact that this the hop-room. Pockets of the choicest varieties are to be seen, and piled around the room they make an imposing array.

Descending to the next floor, a room is entered which is fitted with dropping backs and slate tanks for the storage and preservation of pitching yeast. On reaching the ground-floor one enters a spacious room fitted with three large racking vessels and containing casks of the firm’s beer. Leading out from this is the engine-house, in which is a powerful engine and the pumping machinery mentioned before.

Now descending into the ‘depths of the vault below,’ there are thousands of casks of beer housed. The casks are of different sizes, and each bears hieroglyphics upon them, which the manager would tell the uninitiated were intended to represent the quality and strength of the beer. For instance, in one cellar nothing but bitter beer is kept, and in another only mild beer… Crossing the road at the back, one finds that the firm has cellars there, where there is a large storage of bitter and old beers, and stouts and porters.

Going through the main entrance of this building, a large and spacious room becomes visible, and this is filled with 37 huge vats of malt liquor. Here also is where the famous old beer of the firm is stored. In reaching the offices again a covered yard is passed, where a number of men are engaged in washing casks; and in an adjoining room there is a special engine and fan, erected for the purpose of sending a current of pure air through the casks and thus making them dry and fit for immediate use”

https://forums.pubsgalore.co.uk/archive/index.php/t-35936.html

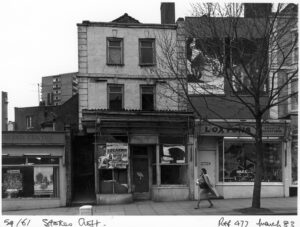

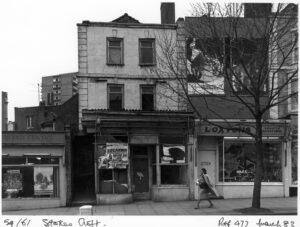

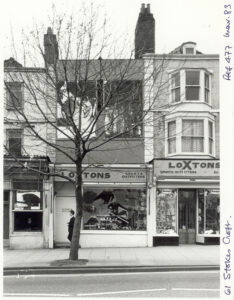

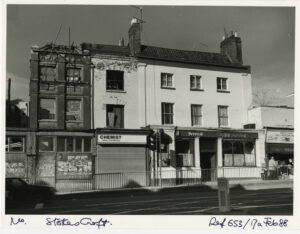

Road widening scheme and neglect

In 1972 the corner building of City Rd and most of the houses on North Street were demolished as part of a road widening scheme. The plan was to turn the road as far as the Arches into a dual carriageway, which would have destroyed the area, but luckily the scheme was abandoned. However, this was one of the factors that led to Stokes Croft becoming neglected during the 70s and 80s, when many buildings were empty and derelict.

In the 80s and 90s, the street was lined with doss-houses, greasy spoons, massage parlours and old codger pubs. There was a series of derelict-looking second-hand shops selling stolen car radios and bikes.

There were some odd characters then… the leather thong man, the poor anorexic girl endlessly running with a giant rucksack on her back, and the formidable old lady Mary was often seen carrying things she’d found back to her second-hand shop in all weathers.

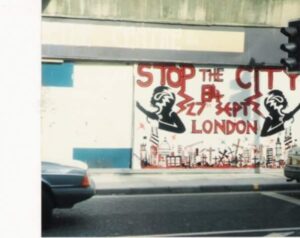

The alternative squat scene thrived during this time: The Demolition Ballroom held punk gigs. The Demolition Diner served food. The Full Marks Bookshop sold left-wing books.