T and J Perry Carriageworks

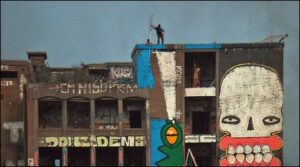

The Carriageworks have long been an icon in Stokes Croft, the delrelict hulk splattered with tagging and graffiti, flanked by the ruined Westmorland house, now revamped into posh flats.

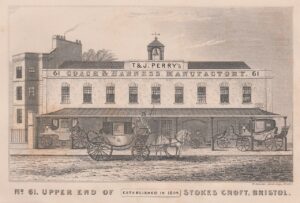

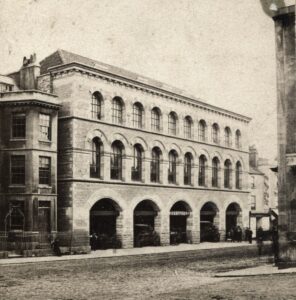

The Carriageworks were built for T&J Perry’s in 1862 to replace a 2 story 1804 carriageworks. The building we can see in Stokes Croft were the showrooms for horse drawn carriages, with a large area of other buildings behind the road for all the stages of manufacture.

The building is a fine example of Bristol Byzantine architecture: a styled based on the striped, rounded Romanesque arches of Venice, but built using native brick and stone, to create a homegrown vernacular style, as an alternative to the gothic revival architecture that was popular in Victorian Britain. The local yellow limestone and dark brick from Cattybrook Brickpit in Almondsbury gave Bristol Byzantine its distinctive striped and colourful style.

Other examples of Bristol Byzantine architecture:

- Brown’s Restaurant on the Triangle

- The Granary in Welsh Back

- The Arnolfini in the Harbourside

- The original Colston Hall building

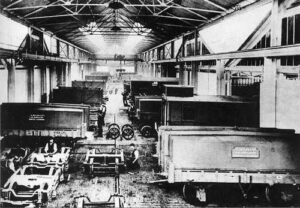

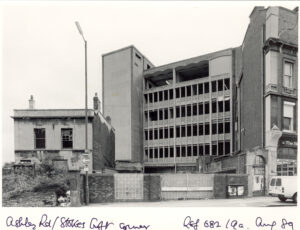

After flourishing during the high-Victorian and Edwardian eras, Perry was facing competition from the new motor car, and converted their showrooms and manufactory to the production of motor cars, before closing down. The building was sold to Anderson’s Bristol Rubber Co. Ltd who operated from 1913 until the 1960s, when it was used briefly by Regional Pools Promotions, before they moved next door to the purpose-built Westmoreland House., leaving the Carriageworks abandoned to decay and dereliction.

A tour around the Carriageworks

Founded in 1804 by T and J Perry, the manufactory covered nearly one and a half acres. The ground floor was a showroom, large enough to hold 30-40 carriages, with offices at the rear which led to a large square yard. Off here was a body-making shop, capable of constructing 6 carriages at a time, one new vehicle being turned out daily. There were also fitting shops, a forge with 8 furnaces, a wood-drying loft and a wheelwrights’ shop, producing both the old elm stock wheels as well as the ‘light, strong and elegant American Warner’ wheels. Completion of the carriages was carried out in the paint-shop, varnishing-shop and trimming-shop, the last concerned with the upholstery and leather work.

At the back was a piece of ground containing a large shed for timber storage, especially of birch board and ash plank. Abutting onto Hepburn Road were reserve stores for the sundry items such as lamps, cushion straps, whip sockets and mats and another for oil, turpentine etc.

As well as the main showroom, Perry’s boasted three others on the floors above, including one solely for two-wheeled vehicles. There were lifts to all the floors.

In the 1890s sixty workmen were employed. Methods were changing with the use of steel and patent indiarubber axle bearings and eventually the carriages gave way to cars. Anderson’s Rubber Company took over the premises in the mid 20th century.

https://www.locallearning.org.uk/carriage.html

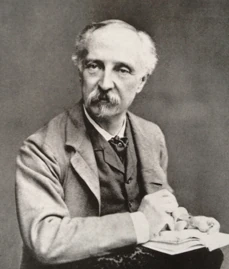

Edward William Godwin

The architect EW Godwin worked in the Ruskin-influenced arts and crafts and Gothic style, also heavily influenced by Japanese design.

His career started in Bristol, where he studied engineering then architecture, designing the Carriageworks before moving to London, where he became friends with Oscar Wilde, Whistler and other progressive writers and artists. He designed artistic furniture, wallpaper and theatrical costumes and scenery, wrote and illustrated books about design and was a leading influence on the Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic movements.

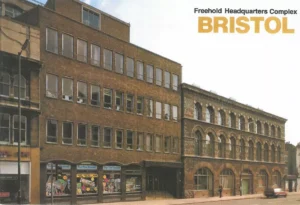

Westmoreland House

Named after and opened by the benefactor Lady Westmoreland in 1966, Westmoreland House was purpose-built to house the headquarters of the Regional Pools Promotions, who raised money for the charity Scope, known originally as the Spastics Society. This popular Pool was known as the Spastics Pool, before the name became a pejorative term. The building was abandoned in 1982 when the organisation got into financial difficulties, and it fell into decay, becoming a dangerous ruin, inhabited by pigeons and homeless people.

Before it was demolished, Westmoreland house had a monumental quality, becoming an icon for the outsider status of Stokes Croft. It made me think of a Neolithic structure like Stonehenge. I used to live on the 11th floor of Armada House and watched the graffiti artists on ladders painting an enormous gummy smile there one day, a piece which grinned down on the revellers and ravers for many years until the eventual demolition and renewal of the building in 2018.

The crocodile was painted by the graff artist Rowdy, the gummy smile and skull by Sweet Toof and Cyclops.

Fancy Pants Curly Wurley Decorative Victorian Shops

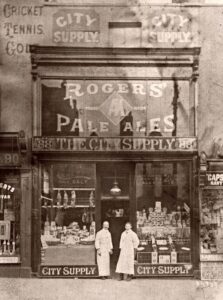

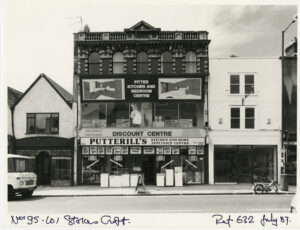

Opposite the bold Arts and Crafts simplicity of the Carriageworks, sits a row of exceedingly decorative Victorian shops.

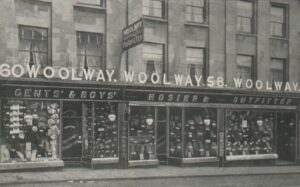

Mass production enabled architects and builders to select decorative features from a catalogue, leading to jumbled house fronts, with decorative curled doorways, window arches and roof parapets all fighting for attention. The Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic movements despaired of the artless jumble of styles, without the sense of individual craftsmanship that they felt modernisation had lost. They looked backwards to an age before mechanisation, admiring the bold simplicity of Gothic and Romanesque architecture, but able to use modern engineering like steel beams to create bigger and bolder spaces. The shops opposite the Carriageworks are prime examples of the lack of design that led architects like Godwin to forge a new style.

However, I really like the exaggerated decoration. It has a unique craziness and shabby aspirational quality that cheers me up, when I look above the shopfronts. The rooftops look like the skyline of a gothic horror movie, oddly juxtaposed by the flats of Dove Street lowering above them in the distance.

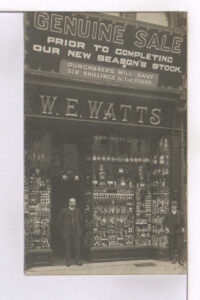

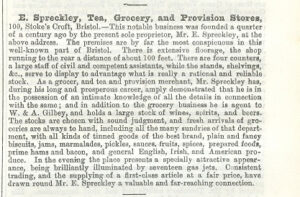

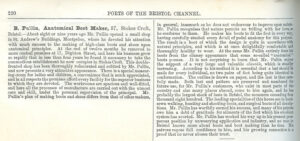

The effusively ostentatious advertising copy for the shops is a fascinating glimpse into the mind of the average customer of that time. The shopkeepers appear to glare out of their shops with fierce pride, standing tall in their freshly starched aprons, and some slouch under lopsided doorframes with tatty windows… It feels like the shops went through rapid phases of change, palatial stores springing up, then changing hands until they ended up converted into smaller shabbier shops as the market changed.

An area that had felt like a pleasant place to stroll and shop became increasingly crowded and urban. The once elegant merchant squares surrounding Stokes croft became converted to industry, and the slopes of Kingsdown were crowded by back-to-backs. As the Edwardian era started, Stokes Croft began to look neglected, in favour of the new shopping areas of Gloucester Road, accessible by the new trams.