Tuckett’s Buildings

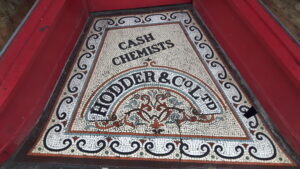

F. Coldstream Tuckett had his grocer’s shop in part of this building until about 1920. The original grocers was very swanky with large rooms. The building was later divided into smaller shops, such as Hodder & Co Cash Chemists.

When Tucketts Buildings were built in the 1890s a number of skeletons were dug up. This was said to have been because there was a gallows here where convicted criminals were hung, or more likely that they were suicides, who were buried at crossroads rather than in consecrated ground.

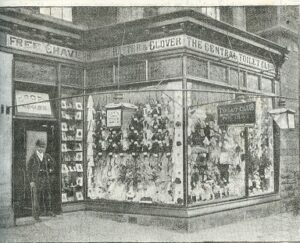

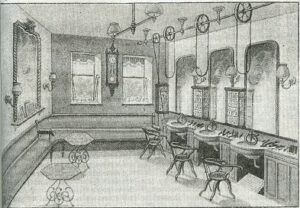

Next door in Croft House was the Central Toilet Club, opened in 1892, owned by the appropriately named Frederick Chave. Croft House was described as ‘one of the most elegant and recherche in the city’, a large private house and Mr Chave (known for his ‘spirited enterprise, genial courtesy and considerable attention to the requirements of his customers’) had ‘transformed it into a perfect palace of luxury and comfort’. It was ‘the only establishment in Bristol lighted by 3 specially constructed lamps whose opal reflectors provided illumination quite equal to electric light’. Among services offered were hair cutting, shaving, shampooing and singeing.

The Civil War Defences and Ma Pugsley

The Civil War:

As a merchant city, Bristol wanted to remain neutral and keep trading at the beginning of the Civil War, and the city leaders were dismayed when Cromwell’s Parliamentary forces took over the city in 1642, but accepted them begrudgingly, swearing the necessary oaths of allegiance to keep their positions.

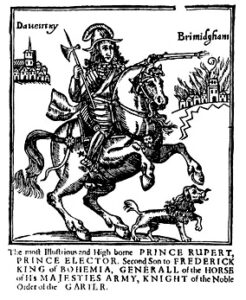

In 1643 Prince Rupert led the Royalist army in storming the city, breaching the defenses and racing down what became Park Street to take the city. For 2 years, Bristol groaned under occupation. Prince Rupert was a young, dashing and handsome commander, but also cruelly indifferent and haughty, and his soldiers took advantage of their power over the citizenry that they had been billeted with.

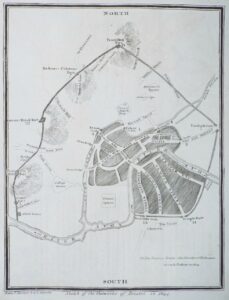

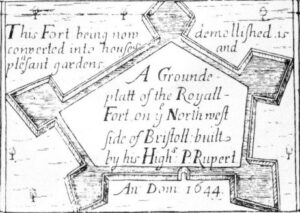

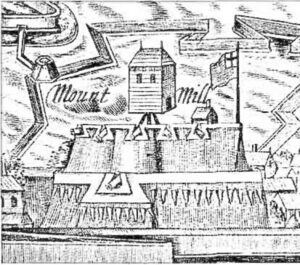

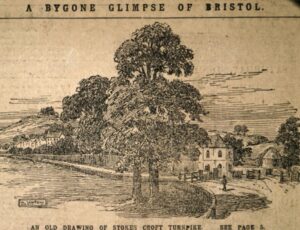

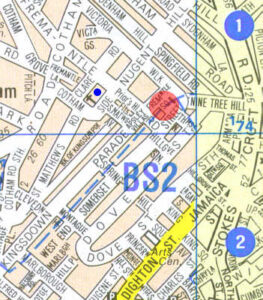

In 1645, Cromwell’s forces besieged Bristol. The city defenses had been rebuilt and a defensive line stretched from the docks to a fort on Brandon Hill. The defenses continued in a line across Park Street up to Royal Fort in Kingsdown, then on to Colston Fort on Kingsdown Parade, and on to Prior’s Hill Fort, situated in Fremantle Square. The defences then ran down Ninetree Hill to Stokes Croft turnpike, then on to Lawford’s Gate by Cabot Circus.

Cromwell’s army needed to breach the defenses at Stokes Croft turnpike to enter the city, but to do so they needed to destroy the guns in Prior’s Hill Fort. The attack took place late at night, when the guns couldn’t accurately fire upon the invaders, who worked by the light of bonfires. The Parliamentarians were supported by canon fire from Monpelier and Cotham. Prior’s Hill Fort had very steep, high walls with portholes to fire muskets, so the battle was long and bloody. Eventually the walls were breached by ladder and fierce and the fort was taken after hours of brutal hand-to-hand combat lasting throughout the night, leaving hundreds dead, strewn across the fields of Kingsdown.

- Detailed description of the Civil War in Bristol: https://brisray.com/bristol/history5.htm

Ma Puglsley:

A very moving tale from these times caught the popular imagination of Bristolians.

A young lady was due to marry the Royalist Captain Pugsley when Cromwell’s attack began. They were hurriedly married by candlelight on the night of the battle in Bristol Cathedral, before young Captain Pugsley had to hurry off to Prior’s Hill to defend the city. In the battle for Prior’s Hill Fort, Captain Puglsey was killed, and buried in a nearby field, next to a spring.

His widow was utterly heartbroken to lose her love on her wedding night, and spent the rest of her long life dressed in mourning, and would walk up to visit the grave of her dead husband every day for the rest of her life.

After the war, people used to visit Kingsdown for the fresh air, away from the fumes and noise of the city, and nannies would take their children there to play. Ma Pugsley, as she became affectionately known, would run around playing and laughing with the children and bathe people’s eyes with the spring water, which was said to have healing properties for the eyes. She became a lovable eccentric, seen every day walking from St Nicholas Gate up to Kingsdown in her widow’s weeds until she died aged 80 in 1705.

She had specified that her funeral should be a happy affair because she would be happy to be finally reunited with her husband. So a fiddler led the procession, playing a merry tune, with girls strewing flowers along the route. She was carried in an open bier, dressed in her wedding dress. 10,000 mourners attended the huge funeral procession, and Ma Pugsley became one of the city’s legendary stories.

Now Ma Pugsley’s well is almost forgotten, lying in a back garden by Nugent Hill, and her story, full of romance, war and undying love is no longer remembered… although her story is an inspiring one.

“Mrs. Pugsley died August 4th, 1700, aged eighty. Her funeral was according to here directions, and was ‘punctually performed to the admiration and in the view of ten thousand spectators.’ Her body was borne uncoffined on a litter, with a sheet for shroud, preceded by a fiddler playing a sprightly air, and two damsels strewing sweet herbs and flowers, while the bells of St. Nicholas church rung a merry peal. Thus it was carried to a grave in a field adjoining Nine-tree hill. Dame Pugsley was supposed to be the widow of a young soldier killed at the siege of Bristol, 1645, and buried with military honours on Nine-tree hill. His widow wore mourning all her life, and desired to be borne to her grave with demonstrations of joy at their happy reunion. Mother Pugsley’s well is within recent memory. It consisted of two stone basins, one of which contained ‘an infallible remedy for the eyes,’ whilst the other was especially renowned for making tea. She built a hut over the spot where her husband fell and was buried, which gave her name to the field and well. At her death she bequeathed money for a sixpenny loaf and a ninepenny loaf at Easter, and a twopenny loaf on Twelfth-day, to each of the sixteen women inhabiting St. Nicholas’ almshouse. The vulgar supposed her to have been a witch, and they trampled upon her grave. A skull, thought to have been her husband’s, was dug up; it had a bullet hole just above the temple.”

Volume III : 1882 Bristol, Past and Present F. Nicholls and John Taylor

- The lost wells of Bristol – Mother Pugsley’s Well, Cotham: https://insearchofholywellsandhealingsprings.wordpress.com/2018/03/19/the-lost-wells-of-bristol-mother-pugsleys-well-cotham/

- Evening Post article about Gammer Pugsley: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/bristol-post/20200804/282389811821182

- Detailed collection of historical descriptions of Ma Pugsley and Pugsley’s Well: https://brisray.com/bristol/pugsley.htm

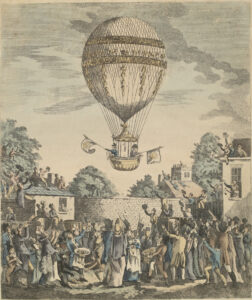

The Balloon Flight of 1810

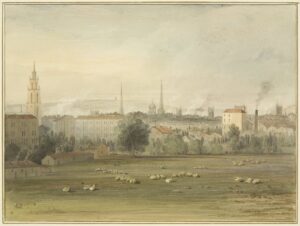

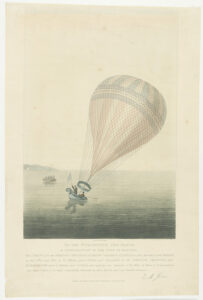

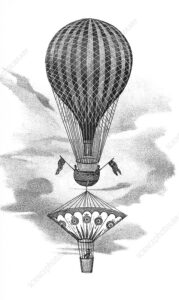

In 1810 James Sadler made an ascent using a hydrogen filled balloon from the fields behind Stokes Croft. The ascent attracted huge crowds and was widely covered by the newspapers.

Sadler took a stray cat with him, which was dropped by parachute over Abbott’s Leigh. The cat survived and was adopted by a physician who named it Balloon.

James Sadler (1751-1828), who as a result of making an ascent from Oxford on October 4th 1784 had become the first Englishman to be taken aloft in a balloon… (made) an ascent, from a field behind Stokes Croft, in Bristol, in which local chemist William Clayfield was carried as a passenger.

The balloon itself was said to be ‘altogether the most magnificent ever exhibited in this country’.

Its envelope was about 30 yards in circumference and made of silk with

gores coloured green and light purple around the middle of which was a circle upon which ‘Right Hon. Wm Windham Greville, Baro de Wotto, Cancel. Univers. Oxon’ was written in gold. The intrepid aeronauts finally took off at around 1.20 pm on what was to be an eventful flight lasting nearly three hours, the balloon initially flying towards ‘Leigh Down’ above which was dropped by parachute a small basket containing a cat, the animal landing none the worse for its experience near Warren House. Here it was retrieved by a lime-burner and subsequently passed into the hands of a local doctor who appropriately christened the creature ‘Balloon’. Sadler and

Clayfield then passed over Clevedon before crossing the Bristol Channel to the vicinity of Barry where, after releasing some of the ballast, the balloon rose rapidly before changing direction and drifting down mid-channel to a rough landing on the sea about four miles off Combe Martin, from where about an hour later both men were rescued by a Lynmouth boat.

https://bristolha.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/bha097.pdf

Ninetree Hill Theatre

There was a theatre on Stokes Croft at the bottom of Ninetree Hill. I can’t find much information about it yet, but the general impression I get is that the Theatre was able to exist because it was beyond the city boundaries. Bristol’s laws against public entertainment were quite harsh and the city leaders were scared of the bad influence of people enjoying themselves… this seems to reinforce the sense that Stokes Croft was outside the city and able to get away with things that weren’t allowed inside Bristol…

The first trace of organised entertainment in a Bristol public house

comes in 1786, when the proprietor of the Old Trout Tavern .in

Cherry Lane off Stokes Croft advertised “Comus’ Court” to be

held on 6 June, when The Gentlemen of the original Catch-Club, Castle-Ditch, have generously offered their kind Assistance for that Night only …

N.B. This Evening is intended to be chearful and harmonious,

with Variety of SONGS by Mr. DEARLE, for his Benefit, being

the last Night of his performing in Bristol. – Admittance One

Shilling, at Eight o’Clock.1

…according to “A Tour through Great Britain” (1761), the old theatre at Stoke’s Croft was converted into an assembly room, and dancing took place there once a week during the winter

The members of the Society of Friends, strongly disapproving of the stage, availed themselves of an Act passed in 1737, by which any person acting in a dramatic piece, in an unlicensed theatre, was liable to be convicted as a rogue and vagabond; and it was intimated that the provisions of the statute would be rigorously enforced. Mr. Champion, the potter, was one of the most ardent of the Quaker opposition, his chief objection to a theatre being the facility for amusement which it offered to the working classes. Another of the dissidents – or perhaps Mr. Champion himself – produced a poem entitled “Bristol Theatre”, printed by the Quakeress, Sarah Farley, in which it was affirmed that the stage tempted men to break all laws, human and divine, and that the results of establishing a theatre would be to entice Bristolians into the paths of misery and vice; truth, trade, and industry would decay together; honest men would turn highwaymen; and the gaol would need enlargement to accommodate the horde of criminals and debtors who would clamour for food at its portal!

https://texts.wishful-thinking.org.uk/Latimer1800/Annals1751.html

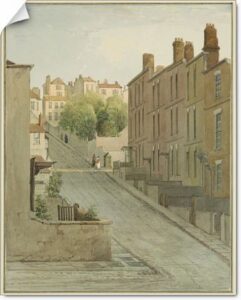

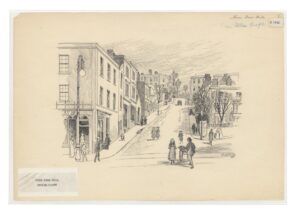

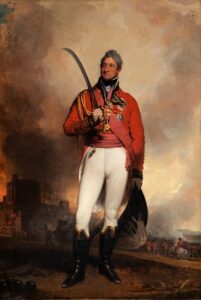

Picton Street

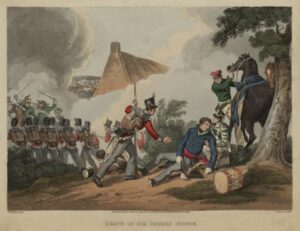

Picton Street was named after Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Picton GCB, a famous general who died leading a bayonet charge at the battle of Waterloo. The street and a public house in the street were named after him in celebration of the battle of Waterloo, which ended 12 years of war against Napoleon in 1815, and the victory gave rise to a surge of patriotism. Picton Street was first created in the 1830s and the pub first opened with his name in 1837. The nearby Wellington Lane and Wellington Place (later renamed Ashley Villas), York Rd and Banner Rd all commemorate generals from Waterloo, since the new suburb of Montpelier was developed shortly after the battle.

General Picton: War hero or monster?

General Picton was regarded as a war hero at the time of Picton Street’s construction, but he had always been a divisive figure.

The Duke of Wellington described him as “a rough foul-mouthed devil, but very capable”.

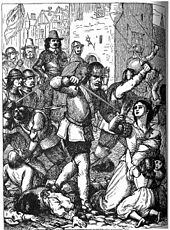

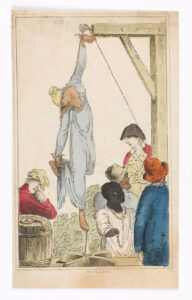

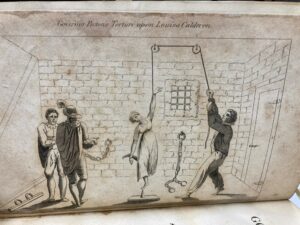

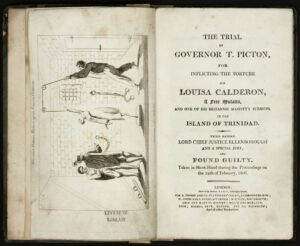

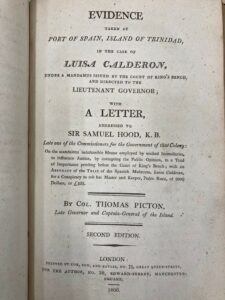

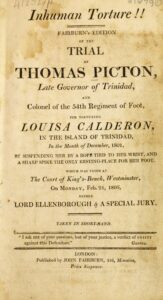

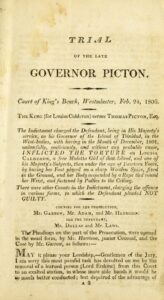

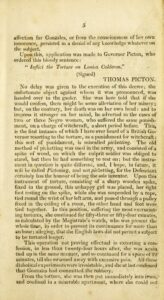

General Picton is most well-known for his brutality in his own lifetime and was known by the aliases ‘The Tyrant of Trinidad’ and ‘The Blood-Stained Governor’ due to his governance of Trinidad and his treatment of slaves. He was taken to court for torturing Louisa Calderon, a free 14-year-old mixed-race girl who was accused of theft. He had ordered the torture known as Picketing, where a person is suspended by a rope from one arm above a pointed wooden block, forcing the victim to put their weight on the spike with their bare feet.

“Her position may be easily described. The great toe was lodged upon a sharp piece of wood, while the opposite wrist was suspended in a pulley, and the other hand and foot were lashed together. Another time the horrid ceremony was repeated, with this difference, that her feet were changed. This practice, I hope, will not in future be called picketing, but Pictoning that it may be recognised by the dreadful appellation which belongs to it. She remained upon the spike three-quarters of an hour, and the next day 22 minutes. She swooned away each time before she was taken down, and was then put into irons called the grillos; which were pieces of iron, with two rings for the feet, fastened to the wall; and in this situation she remained for eight months.”

The printed image circulated through the news caused such disgust that it was instrumental in changing public opinion about slavery. Picton lost the case, but wealthy officers funded his appeal, and the trial was never resolved.

He was also a slave owner, well-known for his brutality against his slaves in Trinidad and his harsh punishments against his own men during the Peninsula War and other campaigns.

After the toppling of Colston’s statue during the Black Lives Matter protests, statues and monuments to Picton in his birthplace in Wales were removed or given more context by new plaques. The origin of the name of Picton Street in Bristol is less well-known, but his portrait hung outside of the old General Picton pub in Picton Street has been removed since the BLM protests.

Louise Calderon:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luisa_Calder%C3%B3n_(torture_victim)

Thomas Picton:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Picton

Fairburn’s edition of the trial of Thomas Picton … Which was tried at the Court of King’s-Bench, Westminster on Monday, Feb. 24, 1806 before Lord Ellenborough & a special jury / Taken in short-hand:

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/e52qa29q/itemsBattle of Waterloo: Thomas Picton, the hero and villain:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-33110128

The removal of Picton’s portrait from Picton Street:

https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/general-thomas-picton-sign-now-4710061

Reframing Picton project:

The museum of Wales commissioned artists to respond to General Picton’s portrait after the Black Lives Matter protests:

https://museum.wales/about-us/Black-lives-matter/reframing-picton/